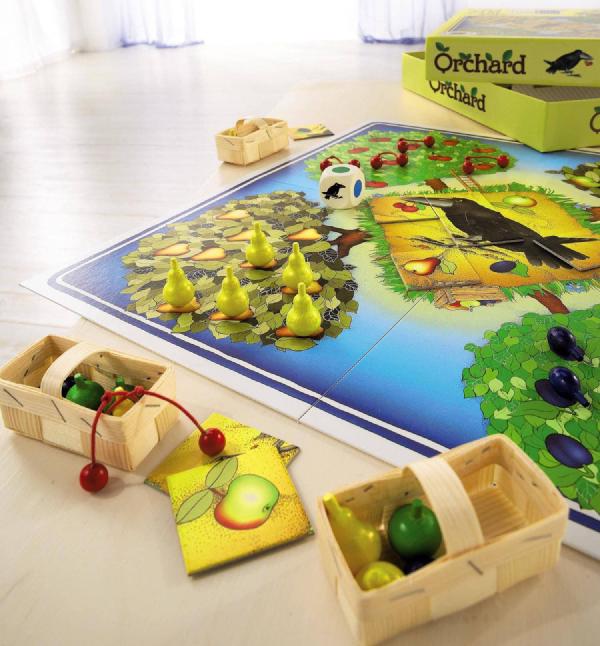

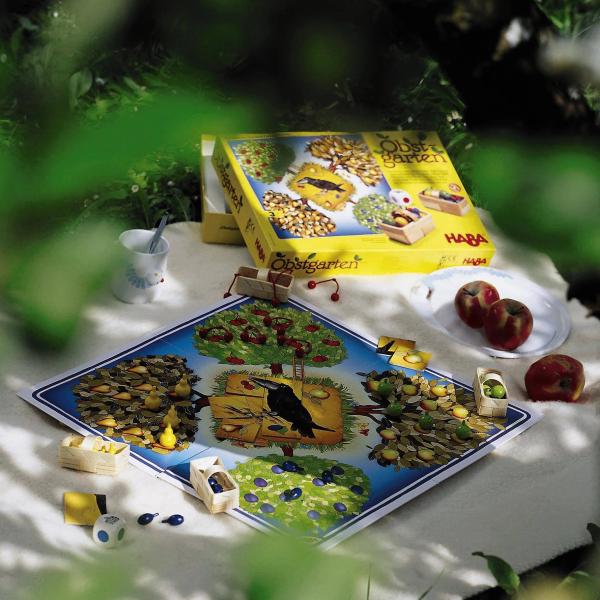

Orchard is a beloved children’s game classic which is so old – it’s as old as myself. 👴 As one might expect from a children’s game, it’s really simple: roll a die, pick a fruit of the corresponding color, and put it in the basket. If you roll the raven, the raven moves one step closer to the orchard. If you manage to pick all the fruit before the raven reaches the orchard, you win together. If the raven reaches the orchard first, you lose.

It’s really quite charming and the fruits make great toys. Kids learn to wait for their turns, to recognise colours and maybe even to accept when they lose. But one thing the game does not teach is making smart decisions: on most turns, the die roll completely determines your action. One die face shows a basket which allows you to pick any fruit you want, but you probably already figured out what’s the dominant strategy: select the fruit we have the most left of. So really, the game offers no meaningful decisions at all.

What makes for a pretty dull game (by adult standards, of course) actually makes for an excellent playground for simulations! The lack of choices means that the probability of winning is completely determined by die rolls, not skills, and hence can be objectively measured. So if you ever wondered how hard it is to beat the raven in that game from your childhood, you’re in for a treat! 🤓

In order to determine the win rate, we can just simulate a series of die rolls and check if their outcome means we win or lose the game. Repeat this process thousands of times and we get a pretty good estimate of the win rate. So without further ado, here’s the win rate for Orchard:

It’s 68.3%. You’re going to win just over two thirds of your games of Orchard.

Is this particularly high or low? It’s actually a really tough challenge in game design to calibrate the win rate of a co-operative game. If you ask people how often they should win a co-operative game for it to be interesting and challenging, they might say something like 50–50, but in reality people simply don’t like losing and would probably be frustrated to play a game where they lose half the time. With that in mind, a game the children will lose 32% of the time seems like a desaster in the making. 😅

A by-product of the simulation is that we can also look at the distribution of game lengths. Here’s a histogram of the lengths of games of Orchard:

So the average game last for about 40 rounds, with a standard deviation of about 5.4, i.e., quite a lot of spread. The shortest possible game would be losing after rolling 9 ravens in a row – the probability of that is \( 6^{-9} \approx 0.00001\% \) or 1 in 10 million games. The shortest possible win would mean rolling the basket 20 times in a row (basket rolls allow you to pick two fruits at once) – which happens in 1 in 3,656,158,440,062,976 games. In theory, the game could go on forever if you keep rolling fruits you’ve already emptied, but honestly, already 40 die rolls without any decisions feels long enough for my taste – in particular when you have to watch a toddler at the same time. 👶

Luckily, there’s a version for even smaller children called First Orchard. Mechanically, it’s almost equivalent except for a few hyperparameter: there’s only 4 of each fruit instead of 10, you only get to pick one fruit on a basket roll and you lose the game after 6 raven rolls,1 but that’s it. How do these changes affect the win rate?

The answer is 76.8%. Expect to win 3 out of 4 games of First Orchard.

When playing with toddlers who rarely have the emotional maturity to handle losing, this seems like a much better win rate. Reducing the number of fruits also cuts the game length in half, much more accomodating for the attention span of a toddler:

Obviously, the win rate will be affected by chosing any of those parameters, but the length of the raven path would probably be the easiest lever to pull if we wanted to make First Orchard as hard as its big sibling. Here’s the win rate for different lengths of the raven path:

Reducing the path by just one step drops the win rate to 63%, i.e., even below that of Orchard, another step reducting would lower it below 50%. For the sake of the peace in our household, I’m glad they’ve found the space in the box for the extra steps. 😅

I’ll leave you with one final thought: as an obsessive data collector, I have logged 68 games of First Orchard, 47 of which we’ve won, i.e., we have a win rate of 69.1%. Our sample isn’t big enough for this difference to be significant (or is it? I’m not going to crunch the numbers now 🤷), but anyways there’s plenty of factors that influence our win rate IRL: my children will rather pick their favourite colour when given a choice than follow the optimal strategy, there was an extra apple in our box (and children emphatically cannot stand leftover components – publishers, take note and stop putting variants in children’s games 😉), their die rolling is far from random, etc. Also, I don’t think we ever really lost a game of First Orchard: when the raven reaches the orchard, my older daughter will just say that the raven flies off to its nest. 🐦⬛ Toddlers… 🤷

PS: You can find the code for the simulations here.

-

The raven path in First Orchard actually has 5 steps, but you start off path and lose when the raven steps off the path into the orchard, i.e., after 6 raven rolls. ↩︎